By Quinn Ranahan, Math Teacher, Montera Middle School, Oakland Unified School District & Agency by Design Oakland Senior Teaching Fellow

Math class is frequently the most challenging for students due to the stigma that there is one way to be smart. If a student doesn’t receive an A in math there’s an immediate jump to thinking they’re not “good” at it. Math smarts can look like many things—changing your mind, taking your time, looking closely, thinking critically, asking questions, or putting yourself out there to get out of your comfort zone.

Last year, the pandemic and Zoom pushed me and my math colleagues to double down in our never-ending quest to help students build a positive math identity. My beginning of the year surveys underscored the importance of our needing to figure out this new form of school; on a scale of one-to-five students were asked “Do you think you’re smart at math?” with 5 meaning “I am smart at math.” Only 52% rated themselves with a four or five and only 13.6% at a five.

“Math smarts can look like many things—changing your mind, taking your time, looking closely, thinking critically, asking questions, or putting yourself out there to get out of your comfort zone.”

A survey of students revealed most students don’t feel they are “smart” at math.

I found myself constantly asking, How can I shift mindsets and make class less intimidating, when it feels like the world is falling apart? How can I create a math space that students do not dread? Over time, I came to understand there were three key parts of my practice that I needed and wanted to push on: Thinking Routines; intentional "humanizing" or connecting with and among students; and a regular exchange of feedback—in both directions.

An example of how Ranahan used the Parts, Purposes, Complexities thinking routine to develop and assess students' understanding of the parts of a virtual software program.

Thinking Routines

Thinking routines provide multiple access points for students. They can be used in the chat, out loud, on paper, or in groups. I also like thinking routines because they give me immediate information on what the students know or understand about the assignment and topic; it asks them to do the heavy lifting and therefore builds their capacity to be independent learners. Furthermore, school settings often give extroverted students praise for raising their hands and being quick to share. Crisis distance learning has provided more space for students who may be introverts, to contribute to class discussions through typing and messaging versus sharing out loud.

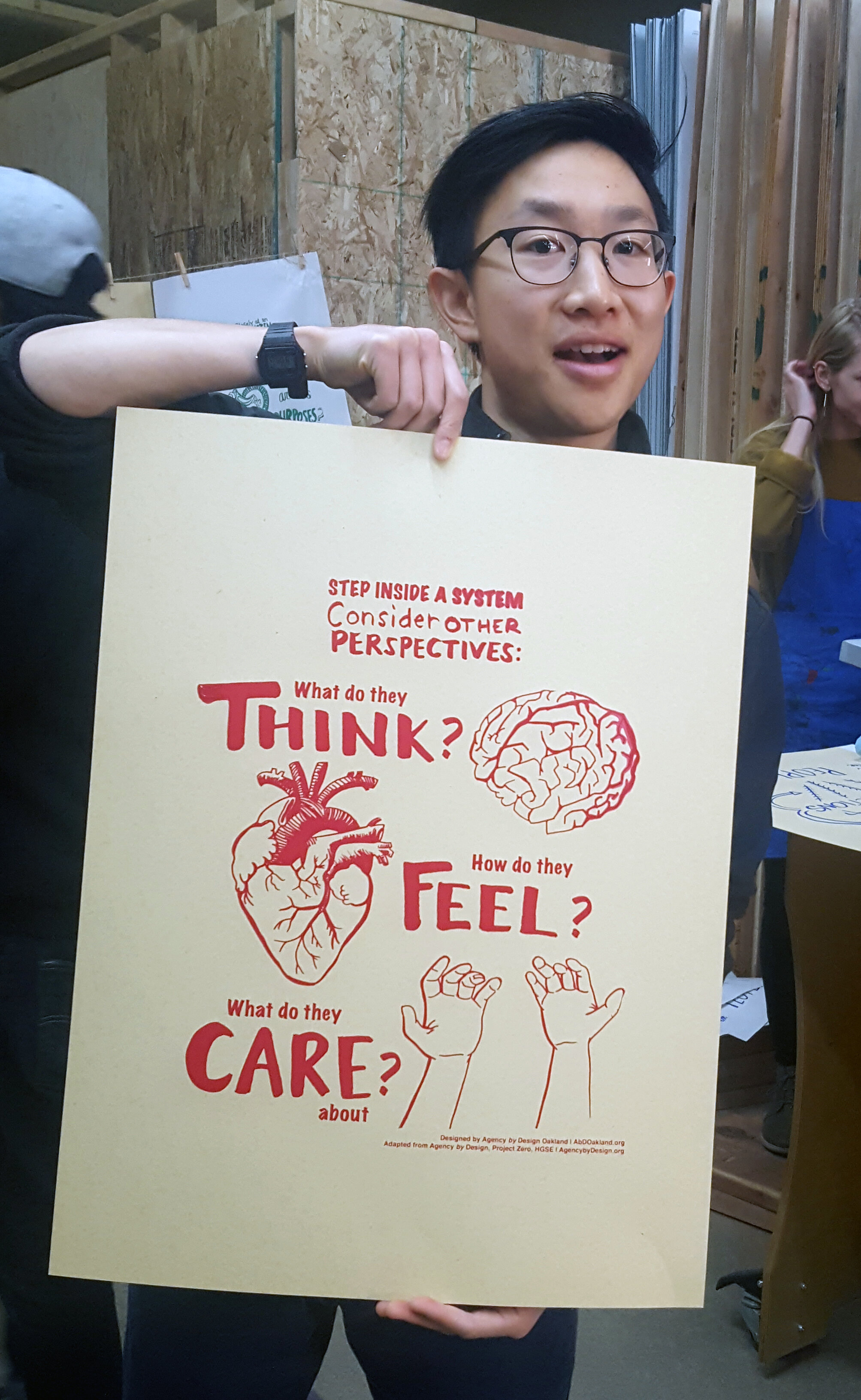

Even in distance learning I continued to use the Parts, Purposes and Complexities from Harvard’s Project Zero, a thinking routine to engage students in breaking apart and looking closely at math systems. I’ve even used it to have students break down parts of a website, so that the confusion of the many buttons are made clear when dissecting and looking closely at each part of the webpage. I asked the questions: What are the parts? What are the purposes of the parts? How do the parts work together? What is the relationship between the parts? How are they connected?

An example of how Ranahan used the Parts, Purposes, Complexities thinking routine to have students look closely at a math equation and explain their thinking.

Humanization & Connection

During distance learning most of my students were represented by small, faceless boxes on Zoom, which is why humanizing and connecting was so important. The intervention strategy I chose to try out was to ask students questions a few times a week that would be fun and/or relevant topics in their personal lives. For example,

Would you rather be a Twitch streamer or YouTuber?

Would you rather eat gummy worms or carrots for the rest of your life?

““I wish my teachers knew that [distance learning] is not ‘the exact same as in person learning,’ it invades much of a child’s personal privacy when teachers guilt-trip students into turning their cameras on and spam the unmute request button after a kid says, “No I can’t turn my mic on.” ”

What I learned from doing this is that slowing down and hearing opinions about different subjects has provided space for students to be themselves and to find joy during a challenging time. Kids that normally never unmuted themselves laughed and joked and had an opinion! Kids that I hadn’t heard from, and who seemed to not have an opinion during math conversations, all of a sudden were awakened and had something to say.

I am still doing this in person; last week during the first week of school I asked the question above about gummy worms & carrots. (Surprisingly, most kids want to be healthy and eat carrots.) But what I realized is so important about these seemingly silly questions is that it gives the kids a place to disagree in a safe way. So that when we get to the math we have already practiced disagreeing and now we can do that and make sense of the math content. It allows them to practice listening to each other’s opinions and reasoning. So not only are these questions a way to humanize and connect; they’re also a scaffold for academic discourse.

Implementation of Feedback

“I wish my teachers knew that [distance learning] is not ‘the exact same as in person learning,’ it invades much of a child's personal privacy when teachers guilt-trip students into turning their cameras on and spam the unmute request button after a kid says, "No I can't turn my mic on." Also it's funny how most teachers are like: "O I carez about ur mental health", and then they give like 19 assignments that are due by the end of the day. Homework is stressful and not fun really- maybe it used to be but now I wonder why school keeps going if it just makes everyone suffer.” - 7th Grade Student

At times it feels like getting feedback is personal and threatens the power dynamic, but getting feedback actually creates trust and agency over learning. When a student provides feedback and it is implemented, there is a slight shift in who has power to impact what class looks and feels like. What I learned from asking my students for their feedback is that you don’t always know until you ask. People want to be heard, students want to be heard and everyone has an opinion. So just asking and getting feedback reinforced that I was listening and it wasn’t an echo chamber of me talking to screens. I did this through written surveys as well as conversation. I remember in one instance the students complained about a teacher talking and saying the same thing over and over again so I asked them if I did that too. They said I didn’t, but I told them to let me know me if I did. So it’s making sure people can share their opinion and inviting students to be heard.

New Year, New Inquiry

All three of these areas that I invested time in supported my students’ experience of distance learning and I plan on leaning into them during in-person teaching as well. Using thinking routines increased participation, in a time when it was difficult to engage in a virtual learning environment. I found success and glimpses of joy when I heard students laugh or spam the chat with their strong opinions about YouTube versus Twitch. And getting feedback allowed me to push through the feeling of being in an echo chamber and it opened a path for students’ opinions to be heard.

As we re-enter the classroom, I’m thinking about the kids for whom distance learning actually worked. Even after just a few days in class I’m noticing that the kids that worked the chat in zoom are still not unmuting themselves in person and I know I have to find new ways to engage those students. There’s a lot more under the surface for those kids—the hand raisers versus the quieter folks who have something they want to share. So I’m thinking about continuing to have more access points, like with thinking routines, but also thinking about other ways. I wonder if this highlighted the safety that they needed in order to learn? So this is the current inquiry on my mind—What will we do for the introverts that thrived on zoom?

Quinn Ranahan just started her 8th year of teaching last week. She is a Math Teacher at Montera Middle School in the Oakland Unified School District, CA.

“I think that creating is liberating. Last year the moments where I felt at peace in Agency by Design Oakland was when I was making and reflecting. I think that maker-centered learning provides many access points for students and as a math teacher that is constantly on the forefront of my brain. Math has so much stigma and maker-centered learning provides space for all types of learners and that is what I am constantly thriving for as an educator.”